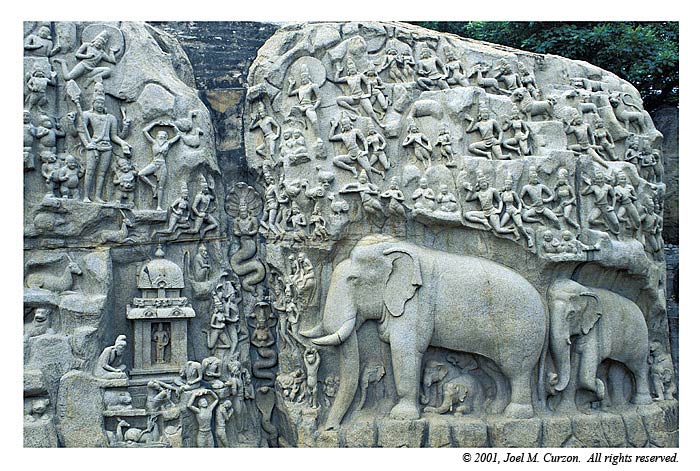

"Descent of the Ganges"---a relief carved into a cliff in Tamil Nadu, India.

I include this as an illustration of the Indian tendency to see the divine in the world rather than separate from it. This relief is sculpted into a large stone monolith, on an impressive scale. It depicts a mythical account of the origin of the Ganges River, which descends from heaven (or from the Himalayas) as a divinity while the whole world, animal and human alike, participates. River divinities in India are frequently personified (if that word can be so applied) as nagas--serpents modeled on India's native cobras. Such myths tend to be understood far less literally, and much more metaphorically, than our myths in the West. This also shows how much less anthropomorphic Indian conceptions of God are than those held in the West, where Abraham's legacy has saddled us with an angry divinity made very much in man's image, separate from the world, and dissatisfied with its fallen state, which he ultimately promises to terminate in a fiery apocalypse.

It is important to note that the Indian philosophical notions just mentioned have not translated into a healthy relationship between Indians and their environment; it is unfortunately true that India's environment is being rapidly degraded by uncontrolled population growth, industrialization, and all the ills typical of a poor, developing country. For that matter, the usual mode of religiosity exhibited in an Indian village is---like the average mode of religiosity in the United States---full of superstition, irrationality, and bigotry. My point, therefore, is not to hold up Hinduism as some kind of pure and benevolent religious belief; rather, it is to note the kernel of a vital idea present in Hinduism, as well as in Buddhism and Taoism: namely, a view that recognizes divinity in the world itself, rather than personifying it as something separate from the world. Or, to speak more clearly, to dispose of the idea of an ultimately real divinity---to reverence the given world and its underlying structure, rather than mythical deities created by the human imagination.